Tasks, Questions, and Practices

By Chandra Hawley Orrill, Posted May 11, 2015 –

We know that to understand how our students think, we need to ask them good questions. We read all the time about the importance of questioning and different kinds of questions. But, all questions are not created equally. In this two-part blog entry, I want to explore the relationship among asking questions, the problems we use in our classrooms, and the effects questions and tasks have on our ability to address some of the Common Core’s Standards for Mathematical Practice (CCSSI 2010). Specifically, let’s think about these Standards of Practice:

SMP 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them

SMP 6. Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others.

SMP 3. Attend to precision.

The goal of this blog post is to emphasize the point that the tasks you choose to use in your classroom enhance or inhibit your ability to ask the kinds of questions that allow students to develop these three Standards for Mathematical Practice (SMPs).

By Chandra Hawley Orrill, Posted May 11, 2015 –

We know that to understand how our students think, we need to ask them good questions. We read all the time about the importance of questioning and different kinds of questions. But, all questions are not created equally. In this two-part blog entry, I want to explore the relationship among asking questions, the problems we use in our classrooms, and the effects questions and tasks have on our ability to address some of the Common Core’s Standards for Mathematical Practice (CCSSI 2010). Specifically, let’s think about these Standards of Practice:

SMP 1. Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them

SMP 6. Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others.

SMP 3. Attend to precision.

The goal of this blog post is to emphasize the point that the tasks you choose to use in your classroom enhance or inhibit your ability to ask the kinds of questions that allow students to develop these three Standards for Mathematical Practice (SMPs).

Tasks Matter

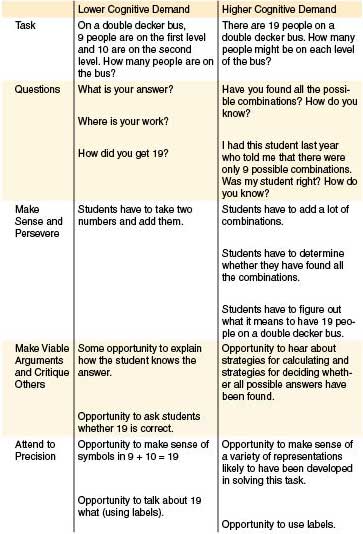

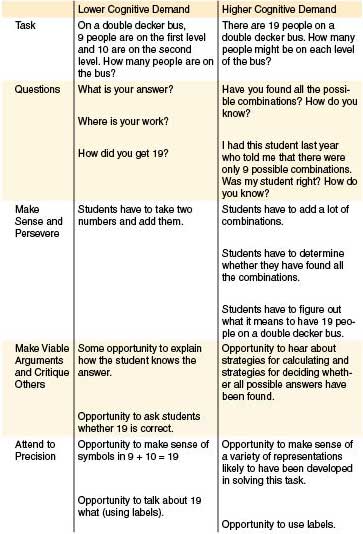

The cognitive demand of a task is the level of cognitive engagement needed to complete the task (Stein et al. 2009). You could think of a problem that requires only memorization as being at the low end of cognitive demand, whereas a task that requires students to make connections between and among mathematical ideas in new ways is a high cognitive demand task. Research has shown that using high cognitive demand tasks in ways that support that rigor will lead to increases in student learning.

The cognitive demand of a task is the level of cognitive engagement needed to complete the task (Stein et al. 2009). You could think of a problem that requires only memorization as being at the low end of cognitive demand, whereas a task that requires students to make connections between and among mathematical ideas in new ways is a high cognitive demand task. Research has shown that using high cognitive demand tasks in ways that support that rigor will lead to increases in student learning.

Questions Matter

To maintain the level of cognitive demand written into a question, a teacher must ask good questions. A high cognitive demand question is one that invites students to explain their thinking, make new connections, describe their process, or critique other ideas. Questions that maintain high cognitive demand engage students in making more sense of the mathematics, whereas questions that lower the cognitive demand focus on correct answers and correct answer paths.

To maintain the level of cognitive demand written into a question, a teacher must ask good questions. A high cognitive demand question is one that invites students to explain their thinking, make new connections, describe their process, or critique other ideas. Questions that maintain high cognitive demand engage students in making more sense of the mathematics, whereas questions that lower the cognitive demand focus on correct answers and correct answer paths.

Standards of Practice Come from Tasks and Questions

One of the challenges of the Common Core is the need to address the SMPs all the time. We all know that students need to actually practice the SMPs to develop the skills and dispositions that are valued. Although forgetting about the SMPs is easy, they are crucial to students’ development as mathematical thinkers. For this discussion, I’ve chosen three SMPs to focus on because they are all closely related to tasks and questions.

• High cognitive demand tasks require students to make sense of them. Unlike a page of simple number sentences, high cognitive demand tasks require that students read them, determine what the question is, and determine how to use the information provided in the task. Sometimes, this is also true of lower cognitive demand tasks.

• High cognitive demand tasks often have multiple ways of finding an answer or multiple correct answers. When this is true, you and your students have much more to talk about. And many more student ideas come out in the conversation. All of this offers an opportunity to make sense of one another’s thinking and for each student to learn how to communicate about her or his own thinking.

• When we engage in meaningful discussions of mathematics that feature a lot of different ideas, it becomes more and more important to be sure everyone in the room knows exactly what each person is talking about. Precision is developed by being asked to make sure everyone understands a viewpoint. It comes from the use of specific mathematical terms, from labeling answers, and from using representations as tools to support communication about mathematics.

One of the challenges of the Common Core is the need to address the SMPs all the time. We all know that students need to actually practice the SMPs to develop the skills and dispositions that are valued. Although forgetting about the SMPs is easy, they are crucial to students’ development as mathematical thinkers. For this discussion, I’ve chosen three SMPs to focus on because they are all closely related to tasks and questions.

• High cognitive demand tasks require students to make sense of them. Unlike a page of simple number sentences, high cognitive demand tasks require that students read them, determine what the question is, and determine how to use the information provided in the task. Sometimes, this is also true of lower cognitive demand tasks.

• High cognitive demand tasks often have multiple ways of finding an answer or multiple correct answers. When this is true, you and your students have much more to talk about. And many more student ideas come out in the conversation. All of this offers an opportunity to make sense of one another’s thinking and for each student to learn how to communicate about her or his own thinking.

• When we engage in meaningful discussions of mathematics that feature a lot of different ideas, it becomes more and more important to be sure everyone in the room knows exactly what each person is talking about. Precision is developed by being asked to make sure everyone understands a viewpoint. It comes from the use of specific mathematical terms, from labeling answers, and from using representations as tools to support communication about mathematics.

Your Turn

Now it’s your turn to think about the effects of Tasks, Questions, and Practices. Consider the two tasks below.

1. Decide which aspects of each task make them of higher or lower cognitive demand. Could you do anything to raise the cognitive demand of either task?

2. Think about questions you could ask students as they work on these tasks. Are these questions raising or lowering the cognitive demand of the task?

3. How does each task attend to perseverance and sense making?

4. How does each task promote making viable arguments? What about critiquing the arguments of others?

5. How does each task provide students with opportunities to communicate in precise ways about mathematics?

Now it’s your turn to think about the effects of Tasks, Questions, and Practices. Consider the two tasks below.

1. Decide which aspects of each task make them of higher or lower cognitive demand. Could you do anything to raise the cognitive demand of either task?

2. Think about questions you could ask students as they work on these tasks. Are these questions raising or lowering the cognitive demand of the task?

3. How does each task attend to perseverance and sense making?

4. How does each task promote making viable arguments? What about critiquing the arguments of others?

5. How does each task provide students with opportunities to communicate in precise ways about mathematics?

Task 1. Lunchroom Problem

Ella would like to buy lunch in the lunchroom today. Meals cost $2.50. Dessert costs an extra 75 cents, and milk costs 75 cents. If Ella has $5.00, can she buy lunch in the lunchroom? (Please See Chart at the bottom of this post.)

Ella would like to buy lunch in the lunchroom today. Meals cost $2.50. Dessert costs an extra 75 cents, and milk costs 75 cents. If Ella has $5.00, can she buy lunch in the lunchroom? (Please See Chart at the bottom of this post.)

Task 2. Buying Lunch

You are going to the amusement park. At the amusement park, you will buy lunch. You don’t want to carry coins, only dollar bills, because coins can fall out of your pocket on the roller coaster. You can purchase any of the items on the menu, but you cannot buy more than one of the same item, and you cannot spend more than $10.00. Using the menu to the left, find out how many different lunches you could buy without receiving any change back.

You are going to the amusement park. At the amusement park, you will buy lunch. You don’t want to carry coins, only dollar bills, because coins can fall out of your pocket on the roller coaster. You can purchase any of the items on the menu, but you cannot buy more than one of the same item, and you cannot spend more than $10.00. Using the menu to the left, find out how many different lunches you could buy without receiving any change back.

More Reading about Cognitively Demanding Mathematical Tasks

National Council for Teachers of Mathematics. 2014. Principles to Action: Ensuring Mathematical Success for All. Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Common Core State Standards Initiative. CCSSI. 2010. Common Core State Standards for Mathematics (CCSSM). Washington, DC: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers. http://www.corestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/Math_Standards.pdf

Stein, Mary Kay, Margaret Schwan Smith, Marjorie A. Henningsen, and Edward A. Silver. 2009. Implementing Standards-Based Mathematics Instruction: A Casebook For Professional Development, 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

Chandra Hawley Orrill, corrill@umassd.edu, is an associate professor and department chairperson in STEM Education and Teacher Development at the University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth. She teaches courses on mathematics content, like proportional reasoning and number sense, for teachers seeking their professional license as well as teaching a variety of courses in the Mathematics Education PhD program. Her interest is in how teachers understand the mathematics they teach and how we can better support teachers in understanding mathematics. She has conducted hundreds of hours of professional development focused on standards-based mathematics and on technology integration in mathematics for elementary school teachers.

Chandra Hawley Orrill, corrill@umassd.edu, is an associate professor and department chairperson in STEM Education and Teacher Development at the University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth. She teaches courses on mathematics content, like proportional reasoning and number sense, for teachers seeking their professional license as well as teaching a variety of courses in the Mathematics Education PhD program. Her interest is in how teachers understand the mathematics they teach and how we can better support teachers in understanding mathematics. She has conducted hundreds of hours of professional development focused on standards-based mathematics and on technology integration in mathematics for elementary school teachers.

This week, I chose to explore high cognitive demand tasks vs. low cognitive demand tasks. I think it is important for children to make connections with the math they are doing. The more the students make connections the more they will appreciate math and keep a growth mindset.

When completing my assignment Problem Set#1, number 8 sparked my interest: Identify the following task as a "low level" or a "high level" cognitive demand task. If the task is considered a "low level" cognitive demand task, rewrite the task so it is a "high level" cognitive demand task.

Solve. 14+___=21

I determined it was a "low level" cognitive demand task, because it is strictly procedural.

I rewrote it:

Blake has merchandise to sell:

2 Salt Lamps

1 Lava Lamp

2 LED Light Bulbs

2 Regular Light Bulbs

Prices:

Salt Lamps cost $21 each

Lava Lamps cost $14 each

LED Light Bulbs cost $7 each

Light Bulbs cost $2 each

Blake sold $21 worth of merchandise. One item sold was a lava lamp. What did he sell with the lava lamp? (1 LED Light bulb)

Going further, I thought of expanding it.

What merchandise and how many of each remained after the $21 dollar sale?

(2 Salt Lamps, 1 LED Light Bulb and 2 Regular Light Bulbs)

In Blake's final sale, he sells all of the remaining merchandise. How much money was needed to purchase all of the merchandise that was left? ($53)

National Council for Teachers of Mathematics. 2014. Principles to Action: Ensuring Mathematical Success for All. Reston, VA: National Council of Teachers of Mathematics.

Common Core State Standards Initiative. CCSSI. 2010. Common Core State Standards for Mathematics (CCSSM). Washington, DC: National Governors Association Center for Best Practices and the Council of Chief State School Officers. http://www.corestandards.org/wp-content/uploads/Math_Standards.pdf

Stein, Mary Kay, Margaret Schwan Smith, Marjorie A. Henningsen, and Edward A. Silver. 2009. Implementing Standards-Based Mathematics Instruction: A Casebook For Professional Development, 2nd ed. New York: Teachers College Press.

Chandra Hawley Orrill, corrill@umassd.edu, is an associate professor and department chairperson in STEM Education and Teacher Development at the University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth. She teaches courses on mathematics content, like proportional reasoning and number sense, for teachers seeking their professional license as well as teaching a variety of courses in the Mathematics Education PhD program. Her interest is in how teachers understand the mathematics they teach and how we can better support teachers in understanding mathematics. She has conducted hundreds of hours of professional development focused on standards-based mathematics and on technology integration in mathematics for elementary school teachers.

Chandra Hawley Orrill, corrill@umassd.edu, is an associate professor and department chairperson in STEM Education and Teacher Development at the University of Massachusetts–Dartmouth. She teaches courses on mathematics content, like proportional reasoning and number sense, for teachers seeking their professional license as well as teaching a variety of courses in the Mathematics Education PhD program. Her interest is in how teachers understand the mathematics they teach and how we can better support teachers in understanding mathematics. She has conducted hundreds of hours of professional development focused on standards-based mathematics and on technology integration in mathematics for elementary school teachers.

This week, I chose to explore high cognitive demand tasks vs. low cognitive demand tasks. I think it is important for children to make connections with the math they are doing. The more the students make connections the more they will appreciate math and keep a growth mindset.

When completing my assignment Problem Set#1, number 8 sparked my interest: Identify the following task as a "low level" or a "high level" cognitive demand task. If the task is considered a "low level" cognitive demand task, rewrite the task so it is a "high level" cognitive demand task.

Solve. 14+___=21

I determined it was a "low level" cognitive demand task, because it is strictly procedural.

I rewrote it:

Blake has merchandise to sell:

2 Salt Lamps

1 Lava Lamp

2 LED Light Bulbs

2 Regular Light Bulbs

Prices:

Salt Lamps cost $21 each

Lava Lamps cost $14 each

LED Light Bulbs cost $7 each

Light Bulbs cost $2 each

Blake sold $21 worth of merchandise. One item sold was a lava lamp. What did he sell with the lava lamp? (1 LED Light bulb)

Going further, I thought of expanding it.

What merchandise and how many of each remained after the $21 dollar sale?

(2 Salt Lamps, 1 LED Light Bulb and 2 Regular Light Bulbs)

In Blake's final sale, he sells all of the remaining merchandise. How much money was needed to purchase all of the merchandise that was left? ($53)